Earlier this week, the Eurydice network – a European Commission initiative devoted to explaining how education systems work throughout the EU – published a new report titled ‘Supporting refugee learners from Ukraine in schools in Europe 2022’. The report synthesises information and policies from 35 countries across Europe (EU Member States except Hungary, plus Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Switzerland, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Norway, and Turkey). A closer look at the information included in the report, together with up-to-date statistics from several Irish State bodies, can give us a sense of how Ireland is working to involve and include children and young people arriving from Ukraine in its educational system.

The Temporary Protection Directive, activated on 4 March in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, includes access to the state education system for all individuals under 18 years old among the guaranteed rights for those granted temporary protection. According to the Eurydice report, in May of this year Ireland had a very high (92%) rate of enrolment of Ukrainian arrivals under 18 in the school system; within the countries studied, this was second only to Luxembourg, at 95%. Countries have taken various approaches to incorporating refugee learners from Ukraine into their educational systems. Ireland, like the majority of European countries, promotes the integration of newly arrived learners into ‘regular’ classes, alongside same-age students from all backgrounds. Language learning and other forms of support are also provided for those who require it. The Department of Education has published extensive guidance for schools about incorporating newly arrived learners, alongside information notes for parents in English, Ukrainian, and Russian.

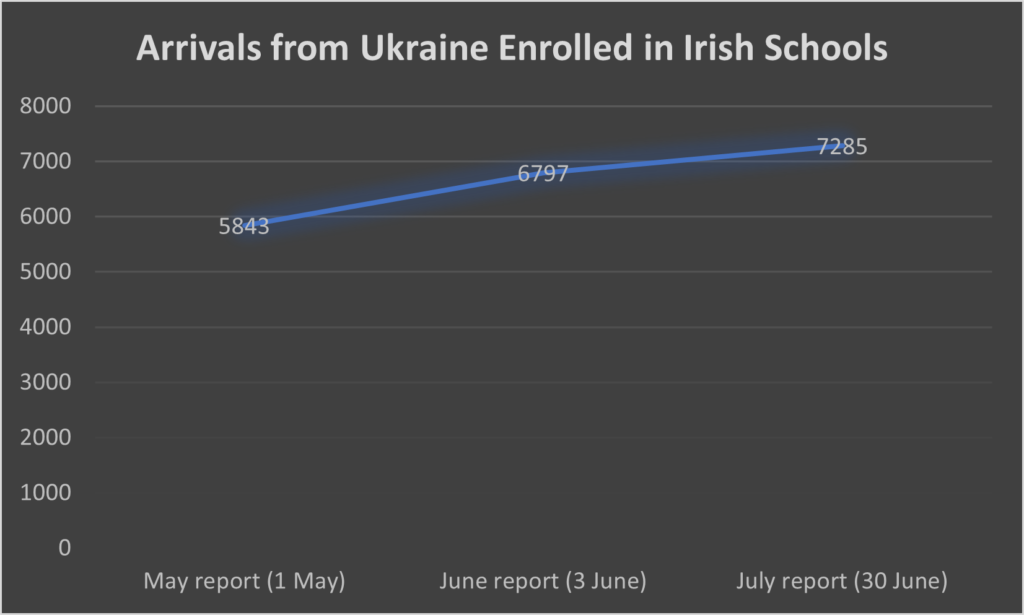

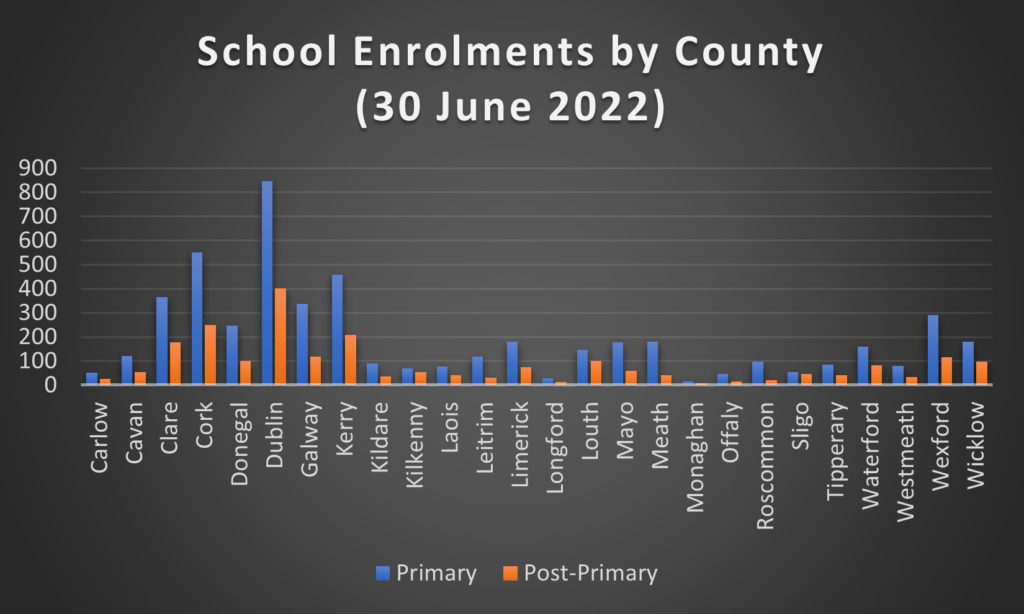

Data from the Department of Education and the Central Statistics Office show that the number of Ukrainian children and young people enrolled in Irish schools has increased steadily since then. The CSO’s most recently published data in the series ‘Arrivals from Ukraine in Ireland’ show that 37% of arrivals up to 19 June were children and young people aged 0-19. Of those enrolled in school, 71% were in primary education and 29% in secondary education. The Department of Education’s monthly announcements of enrolments of Ukrainian students (from May, June, and July; the May statistics are the ones used in the Eurydice report) demonstrate a steady increase in total number of pupils, and show their geographical distribution across the twenty-six counties:

A previous Eurydice report highlighted some of the social barriers that new arrivals (from any background) may face in Ireland. The 2019 report noted that students from migrant backgrounds tend to experience higher rates of bullying in schools. Throughout Europe, students who do not speak the language of instruction at home report feeling a lower sense of belonging and experiencing more bullying. While for most European countries, there is little variance in these reports based on whether the student was born within the country or elsewhere, in Ireland foreign-born students report being bullied more often than those born in Ireland.

A ESRI report published in March 2022 used data from the Growing Up in Ireland study to examine self-concept among children born in Ireland for whom at least one parent was born abroad. (The self-concept score is used in the report as a measure of wellbeing. This measurement consists of six subscales: happiness, popularity, freedom from anxiety, physical self-image, intellectual/educational self-image, and behavioural self-image.) Some migrant-origin groups were found to have lower average self-concept scores than children with Irish-born parents; the analysis shows that for some of these groups, including those of Eastern European (including Ukrainian) origin, these scores were mediated by social factors such as lower participation in sports and social and cultural activities. Participation in team sports was consistently associated with higher self-concept, regardless of the child’s family background.

While the data used in the 2019 Eurydice and 2022 ESRI reports do not include or account for new arrivals from Ukraine, and thus we cannot say with certainty that newly arrived learners from Ukraine will have similar experiences, they provide insight into factors that may affect these children and young people’s sense of wellbeing, belonging, inclusion, and safety within Irish schools in the upcoming academic year.

For more information, see:

Eurydice, Supporting refugee learners from Ukraine in schools in Europe 2022 – press release

Eurydice, Supporting refugee learners from Ukraine in schools in Europe 2022 – full report

Eurydice, Integrating students from migrant backgrounds into Schools in Europe

ESRI, Children of migrants in Ireland: how are they faring?

Department of Education, Information for schools – Ukraine (information in English, Ukrainian, and Russian)